The Haftarah of Va’Eira (Linear Annotated Translation of the Haftarah of Va’Eira) is from the prophet Yechezkel, who addresses Egypt, and calls Pharaoh a “crocodile”. In the Parsha, G-d tells Moshe and Aharon to make a “sign” for Pharaoh: Aharon’s staff turns into a crocodile.

Why crocodiles?

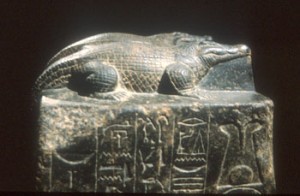

The crocodile was the symbol of the Egyptian god of the Nile:

Rabbi Natan Slifkin, the “Zoo Rabbi”, explains why:

Crocodiles are the largest of reptiles. They can measure well over twenty feet in length, they account for more human deaths than any other large animal killing around a thousand people in Africa annually…A crocodile’s sense of smell is very acute, and its hearing is also excellent. It can detect the vibrations of a mammal moving around near the water’s edge. … The crocodile will submerge, and without a ripple in the water, it will cruise towards its prey. It knows exactly when the animal is approaching the water, and at that precise moment, it strikes. The crocodile’s powerful tail drives it forwards and it explodes out of the water like a missile. Once it has gripped onto its prey with its 66 teeth, there is little chance of escape. Larger prey is first drowned and then broken up into swallowable chunks. The crocodile breaks up a carcass by seizing a limb or part of the body and spinning on a horizontal axis. Using this method they have been known to spin a leg off a human at the hip. The prey is swallowed without chewing; their stomachs are the most acidic recorded for any vertebrate, allowing them to digest even the bones and shells of prey animals. … The Egyptians worshipped the crocodile, and they embalmed hundreds of them, after which they were wrapped in strips of cloth, just as the humans of the time. (The Power of Crocodiles)

In the Haftarah, Yehezkel quotes Pharaoh as saying, “The Nile is mine, and I made it”, reflecting Egypt’s attitude of invincibility and omnipotence. And G-d’s response is, roughly speaking: “I’ll show you who’s omnipotent, you arrogant reptile!” (Roughly. See the text for details.) Likewise, in the Parsha, when Aharon makes his staff turn into a crocodile, and so do Pharaoh’s magicians, Aharon’s crocodile eats the others. The Midrash says:

“Hashem said, this arrogant villain calls himself a crocodile? Go and tell him, “You see how this staff is a dry stick and turns into a crocodile, and can move and breathe, and swallows all those other staffs, but eventually it goes back to being a dry stick? You, too – I made you from a drop of liquid, and I gave you the kingdom, and you boasted and said “The Nile is mine and I made it”?! I’ll turn you back to nothingness and chaos. You swallowed all the staffs of the tribes of Israel, I will cause you to disgorge all that you have swallowed!” (Yalkut Shimoni Va’eira 181)

Turns out, G-d doesn’t like it when people think they’re invincible.

A deeper connection where the Haftarah sheds light on the Parsha: Va’Eira: Knowing Hashem

Copyright © Kira Sirote

In memory of my father, Peter Rozenberg, z”l

לעילוי נשמת אבי מורי פנחס בן נתן נטע ז”ל